Behind the Book

Walt Whitman

Voices in Poetry series

NOTE: This is a slightly revised essay that appeared on the Children's Literature Network website in 2010.

(Sadly, CLN is no more.)

(Sadly, CLN is no more.)

I will get to the poetry, I promise. But first, a few words about sports.

Back in the early 1990s, I worked as an editor for The Creative Company, a children’s educational book publisher in Mankato, Minnesota. Every year the company put out a series of books devoted to one of the major professional sports: baseball, football, basketball, and hockey. Every team got its own book. Some editors would have enjoyed this assignment, but I’m the sort who’d have to be bonked on the head with a ball before I’d notice that world. My approach to sports has always been to simply feign mild interest whenever the people around me start exulting or grousing about how their teams are doing.

I don’t remember which sports series I was working on in 1993. But whether the series involved a big ball, a little ball, an oblong ball, or a rubber disk and a stick, these statements apply:

- The books contained lots of names and lots of numbers—names and numbers that had to be checked and double-checked.

- The books contained a lot of jargon. This isn’t a disparaging comment, by the way. Jargon can be a useful shortcut for people who share an understanding of a subject. I learned this lesson when, as an English major, I balked at using the word “winningest.” I was sure it was the invention of a quirky author. But when I actually took a look at the sports section and saw that the word was commonly used, I came around. (I later learned that the first known use of “winningest” was in 1972. The word was just eight years younger than I was. No wonder I was skeptical!)

- There were a lot of books in each series. For the NHL at that time, 26. For the NBA, 27. For the NFL and MLB, 28.

Each one of these books would have to be edited and sent back to the author. Some of the authors were old pros and required little guidance, but a few of them just didn’t get the format. The manuscripts went back and forth between us. Back and forth, like playing catch with a big, heavy ball, in slow motion. (I hope you’ll notice that I used a sports simile just now.) Then came proofreading the galleys. Then came proofreading the layouts.

Oh, and did I mention photo captions? Sidebars? Cover copy? Catalog copy?

But this piece is not about sports books.

It’s about poetry.

In the middle of my NHL, or NBA, or MLB, or NHL woes (I truly don’t remember), my boss gave me a new assignment. He wanted to publish a young adult poetry series featuring the work of major American poets. I could develop the concept myself.

To use another sports metaphor, my team had just been given first pick in the draft.

I hired another freelancer (hey there, Barrie!) to help determine which poets to include and to provide me with a rough cut of the poems most likely to appeal to junior high kids. And then I gave myself the assignment of putting together the first book, as a prototype.

My main goal for the Voices in Poetry series was that it be engaging, not only for would-be English nerds but also for readers who were daunted by poetry. I wanted to show the poet as a real person, and to make a connection between that real person and his or her work.

I settled on a format of biography interspersed with poetry. The biographical sections would cover specific periods or themes, and would fit on one page. They would be given simple, strong titles. The poetry that followed would relate in some way to that part of the poet’s life. If readers wanted to read the biography first and then go back to the poetry, or vice versa, it would be easy enough to do.

I also wanted to include biographical pictures, maybe with a photo section at the beginning and end. But buying the rights to pictures and printing them would mean a bigger financial commitment from the publisher. That wasn’t my decision to make.

Walt Whitman—the “poet of the people”—was my subject. I’d edit or proofread a sports book, then reward myself with an hour or two of work on the Whitman book. The clear-eyed buoyancy of his voice and the pioneering spirit of the man himself gave a lift and lilt to my days.

My boss liked the concept and sent my manuscript to his designer. And what she came up with was extraordinary.

I’d hoped for a few pictures and a clean design. What I got was pure luxury.

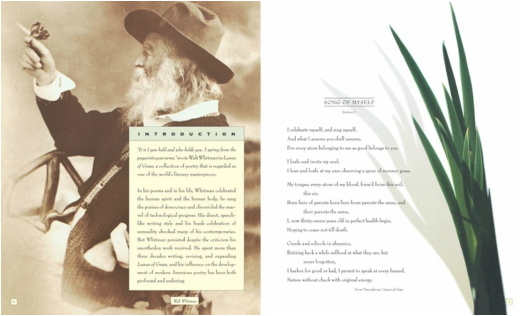

Every biographical segment had an archival photo in a full bleed off the page.

Every poem was illustrated with art—in this case, images of leaves.

To publish such a book would mean a major investment in design, illustration, and printing. And to publish a whole series of books in that format—knowing that no book of poetry, no matter how engaging or lovely, would ever sell half as many copies as a book on the Boston Red Sox or L.A. Lakers—was, to me, a noble decision.

Essentially, the sports books made the poetry books possible. And I like to think that the sports books convinced a lot of kids, boys especially, that reading was something worthwhile to do—and that, having become readers, maybe a few of them decided that poetry was pretty cool, too.

Walt Whitman was published in 1994. It was named to the New York Public Library’s “Best Books for the Teen Age” and received a starred review in School Library Journal. It also won a Parents’ Choice Illustration award. It stayed in print for nearly 20 years.

I’ll always have a special fondness for Walt Whitman and the entire Voices in Poetry series (Robert Frost, Emily Dickinson, Marianne Moore, Sylvia Plath, Langston Hughes, e .e. cummings, and many more that were published long after my time with the Creative Company). I saw my idea not only accepted and given shape, but enlarged in a way that I would never have dreamed possible.

Truly, books are communal undertakings.